|

| Cool Bob, 1966 |

Like many a 1960s classic album, Blonde On Blonde is a record that is very much of its time, but one that still resonates down the years as an important milestone in rock music.

It marked the end of an era for Dylan himself, the culmination of two years of intensive writing, recording and touring that could have turned him into another rock and roll casualty. He was too smart to fall into that trap, though. Or maybe he was just lucky.

In 1965, Bob Dylan had consolidated his move into electric music with the album ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ and its iconic single ‘Like A Rolling Stone’. He had toured Europe, confronting the hostility towards his new electric sound from folk purists who called him Judas for abandoning the protest movement and his acoustic guitar.

In his contemporary review of Blonde on Blonde for Crawdaddy magazine in July 1966, Paul Williams had words for those who continued to boo Dylan at his live shows.

|

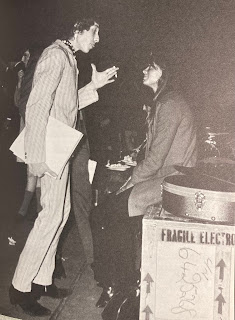

| Electric Bob, cool suit |

By the end of 1966, Dylan would be in hiding, burnt out from the road and keen to embrace family life. But as the year opened, he was on top of the world commercially. He had sold 10 million records worldwide and had begun recording a double album (a first in the rock era) that would be the culmination of his early 60s rise to stardom.

On Blonde On Blonde, in contrast to his previous albums, two things stood out for Paul Williams: “the uniform high quality of the songs chosen for this extra-long LP and the wonderful, wonderful accompaniments.”Recording sessions had begun in New York in October 1965, but whatever Dylan was looking for, he wasn’t getting it from these sessions. His producer Bob Johnston recognised that Bob wanted to craft an album with greater refinement than his previous efforts. Organist Al Kooper and guitarist Robbie Robertson were retained from the New York dates and in early 1966, the sessions moved to the CBS studios in Nashville, using their highly experienced session players.

“Not only is Dylan’s present band easily the best backup band in the country, but they appear able to read his mind,” said Williams. “On this album, they almost inevitably do the right thing at the right time. They do perfect justice to each of his songs, and that is by no means a minor accomplishment.”

|

| My vinyl copy is an original 1966 UK CBS version, with inner sleeves advertising Andy Williams and Doris Day alongside Dylan, The Byrds and Miles Davis. |

At the first Nashville session on Valentine’s night, Dylan recorded a keeper version of ‘Visions of Johanna’, side one track 3 of the original vinyl. Dylan biographer Greil Marcus suggested the song had been written during the blackout that shut down New York in November 1965, which might explain lines like “the heat pipes just cough” and “lights flicker in the opposite loft”.

When people refer to this song as an example of Dylan’s genius, it’s down to the atmosphere he creates with the lyrics and their delivery.

"Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial

Voices echo, 'this is what salvation must be like after

a while'

But Mona Lisa musta had the highway blues

You can tell by the way she smiles"

While folkies complained that he wouldn’t sing ‘Blowin’

In The Wind’ any more, rock fans puzzled over the meaning of these new words. Dylan's command of language and his own skewed and playful lyrics were a key part of the intrigue - and he wasn't about to enlighten anyone as to their meaning.

"Only when it is amplified by music and declamation," wrote the poet Gerard Malanga, "does Dylan's verse stand forth in all its living strength and beauty. In the subtle distinction of its peculiar rhythm...an entirely new language prevails."

On 'Memphis Blues Again', Dylan relates specific episodes and emotions in his offhand, impressionistic manner.

Well, Shakespeare, he’s in the alley

With his pointed shoes and his bells

Speaking to some French girl

Who says she knows me well

And I would send a message

To find out if she’s talked

But the post office has been stolen

And the mailbox is locked

Oh, Mama, can this really be the end

To be stuck inside of Mobile

With the Memphis blues again

Contemporary reviews referred to Dylan as a poet - how he "knew" and how he was "telling it like it is". But as NME writer Mick Farren admitted in a retrospective mid-1970s assessment of Blonde On Blonde, "If Dylan was really telling it like it is, we'd all know exactly what he was talking about. We wouldn't have been sifting through his symbolism, in the vain attempt to find his particular Rosebud." That sifting has only intensified in the intervening 50 years.

|

| The gatefold of Blonde on Blonde and the NME reassessment by Mick Farren |

It’s not just the words though. Credit must go to the musicians for providing such sympathetic accompaniment. The keyboards and the guitar playing, the bass and drums are all excellent. That must have been inspiring to Dylan himself, pushing him to produce his best work.

“Blonde on Blonde is - in the quality of the sound, the decisions as to what goes where, the mixing of the tracks, the timing - one of the best-produced records I’ve ever heard. Producer Bob Johnston deserves immortality at least,” said Williams in his ’66 review.

|

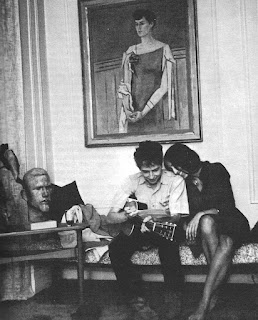

| Bob and Joan Baez |

Blonde On Blonde has a handful of truly romantic songs that stand today as classics, where the tenderness outweighs the bitterness; notably I Want You, Just Like A Woman and Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. The day after recording ‘Visions of Johanna’, the session for Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands began at 6 pm, but Dylan hadn’t finished the words. Finally, at 4 am, the musicians assembled for a take. This link has them working out an arrangement.

Though they were reasonably familiar with the song, the band hadn’t appreciated it would run for almost 12 minutes. Drummer Kenny Buttrey recalled they'd be looking at each other thinking, “man, this is it, this is gonna be the last chorus and we've gotta put everything into it we can. We're cracking up. I mean, we peaked five minutes ago.”

Part of the intrigue of the romantic songs on Blonde On

Blonde was who Dylan was writing about - it could often be Joan Baez, on ‘Sooner Or Later’ or ‘4th Time Around’, for example. Dylan

later acknowledged the debt he owed to Baez - who nurtured his career early on - but he did a poor job of repaying it in

1965, when Joan accompanied him to the UK.

You feel for her, watching the movie 'Don't Look Back'. the film about Dylan's UK tour in April 1965. By this time, Bob was already involved with Sara Lownds, but he hadn't told Joan. It was Sara, while working at the film production division of Time Life, who had

introduced Dylan to D.A. Pennebaker, the director of Don't Look Back. It must have been humiliating for Baez, realising she'd made a big mistake in coming on that tour.

|

| Sara poses for an unused version of the Highway 61 album cover |

.Bob would later say he was just trying to deal with the craziness of his life at that point; and it was crazy. Joan should never have gone with him to the UK. She described it as hell (everyone else was on drugs - she was straight). And Bob didn't - as she had expected - reciprocate Joan's generosity by inviting her onstage to perform with him.

Bob and Sara married in secret in November 1965. On ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of

the Lowlands’, it was his new wife he was serenading.

In his book 'Bob Dylan - An illustrated history', Michael Gross called Blonde On Blonde "letter-perfect rock and roll. Here was an album with a song that lasted a whole side. The symbolism was Dylan's but the situations were everyone's. If any one disc recorded in the Sixties can stand as a psycho-historical recreation of the times, this is it.

"With its passionate love songs and descents into Dylan's dramatic, urban landscape, is not an album to pin down. Like the ‘ghost of electricity, howling in the bones of her face,’ it is more something to feel.”

The first single from Blonde On Blonde in April 1966 saw Dylan being as plain as could be about smoking marijuana, while also deflecting to avoid censure. Knowing that a song called ‘Everybody Must Get Stoned’ might be banned before it even got out of the traps, he called the song ‘Rainy Day Women #12 & 35’.

In The Rolling Thunder Logbook, Sam Shepard quotes a character called Johnny Dark saying, “I couldn’t believe it the first time I saw ‘Everybody must get stoned’ on the jukebox. I mean there it was, right in front of everybody. Right there in the restaurant. I couldn’t believe you could play that kind of stuff in public while you were eating your cheeseburger.”

Regardless of the cryptic title, it’s a wonder the song wasn’t banned anyway. It did inevitably fall foul of conservative programmers at some radio stations in the US and it was excluded from playlists at the BBC. But exposure on pirate radio stations was sufficient to see it rise to No. 7 in the UK. It made it all the way to No. 2 in the US.

|

| With Francoise Hardy, 1966 |

"One of the main problems approaching Blonde On Blonde after all this time (my italics) is the temptation to take the whole thing far too reverently," said Farren in 1976.

Indeed, so here we are, another fifty years down the track and the album is still resonating.

The playfulness and wilful surrealism of some of Dylan's imagery doesn’t detract from the power and fascination of this record. Even as a teenager, I could tell this was something to get lost in. Blonde On Blonde was the first Bob Dylan album I bought and it was another of those records that fired my imagination. Did I get the full message on those first listens? Certainly not, but what I did hear was an atmosphere and a sense that this music really had depth to it. I was tapping into an unattainable bohemian lifestyle.

In his book ‘The Ballad of Bob Dylan’, Daniel Mark Epstein described seeing Dylan’s comeback show at Madison Square Garden in 1974. “Now, at the age of 25, I could understand lyrics that meant little to me when I heard them at 17. Poetry grows with you.”

In the year when punk rock broke through in the UK, Farren was still in awe of Dylan's achievement 10 years earlier.

"It is certainly Bob Dylan's finest hour and there are less than a handful of other works that can seriously challenge it for the title of the greatest rock album of all time."

In fact, a year earlier, the NME writers had judged it to be, in their collective wisdom, the second greatest album ever, after Sgt Pepper.

In April 1966, Dylan’s friend Richard Fariña died in a motorcycle accident in California, just as he was launching his first novel. It was his partner Mimi Baez’s 21st birthday. Tragic in every way.

Three months later, Dylan came off his bike near

his home in Woodstock, New York. He knew he could have died on his

motorcycle, as Fariña had.

Ironically, the accident offered him the perfect

excuse to go into hiding.

Dylan wrote, in his memoir, Chronicles, Vol 1: “I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race. Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on. Outside of my family, nothing held any real interest for me and I was seeing everything through different glasses.”

In his excellent book ‘Positively 4th Street’, about how the lives of Bob, Joan, Mimi and Richard had intertwined, David Hadju wrote: “For a year and a half after the accident, Dylan stayed in seclusion in Woodstock, while rock musicians absorbed and drew upon his ideas.

“The trio of records uniting poetry with elements of folk and rock and roll – Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and the double Blonde On Blonde, came to be acknowledged as pop masterworks and charted a whole new style of music.

“When Dylan began making music again, it was wholly for his own pleasure.”

He made very few public appearances once Blonde On Blonde was released and did not tour again for almost eight years.

Here's Dylan on the 1966 UK tour, singing 'Visions of Johanna' unaccompanied.

IF YOU LIKE MY BLOG, PLEASE HIT THE FOLLOW BUTTON ON THE SIDE PANEL THANKS

Also on this Blog:

No comments:

Post a Comment