|

| The Beatles in '66 |

"You clink a couple of glasses together, or take bleeps from the radio, then you loop the tape to repeat the noises at intervals."

By 1966, the Beatles' music was starting to reflect their indulgence in marijuana and LSD. The extra time the band would have in the studio led to a much greater level of experimentation. The first fruits of this psychedelic vision appeared on Revolver in August 1966. It has come to be seen as their high point, musically.

The band had begun recording sessions in the Spring of 1966, at a

time when they were still playing live. They played their final show on

August 29 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, concluding that they

were stagnating as a band because they couldn't be heard above the

screaming.

In his interview for the 20th anniversary of Rolling Stone magazine, George Harrison said he had wanted to stop touring in 1965.

|

| The NME's reappraisal in 1976 |

The retrospective review of Revolver by the NME's Steve Clarke in 1976 (pictured here - click on it to read the clipping) reflects a growing appreciation of it as "their most listenable and durable work".

Revolver was still largely a Lennon and McCartney show, but George was tangibly more involved at this point, contributing three songs including the opening track 'Taxman' - "a tight, spare rocker," said the NME. Clarke notes how the band had evolved as players, with Paul's bass lines being "vibrant and imaginative" and the guitars harder and louder.

In the mid 60s, the majority of vinyl albums were still released principally in mono. Stereo was emerging but for bands like The Beatles it was still an afterthought. There were mono and stereo versions of Revolver released and the mixes were often very different between the two formats.

For example, on Taxman, the mono version gives more prominence to the bass guitar and John's rhythm guitar has more attack. A cowbell appears prominently in mono but is buried in the stereo version.

While John's songs reflected his increasingly cerebral

preoccupations, Paul's work on Revolver showed a classic songwriter in

the making. Songs such as Here, There and Everywhere, For No One and Eleanor Rigby would become standards covered by many other artists.

Eleanor Rigby is such a unique but assured piece of work, really one of their best compositions - probably more Paul than John but once again proof of their potency as a writing partnership.

The psychedelia is turned up a notch for John's 'I'm Only Sleeping', with its dreamy feel the result of vari-speeding of the vocals and rhythm track, and some 'backwards' guitar (actually written out backwards and played as a melodic run by George). |

| The Fabs pay the price for standing up Imelda |

World tours interrupted the sessions. On one leg of the tour, in the Philippines, the band failed to attend a reception arranged for them at the Presidential Palace by Imelda Marcos. "I'm very pleased to say that we never went to see those awful Marcoses," said George.

"They sent people out there to beat us up. We couldn't even get a car ride to the airport. After half the people with us were beaten up, we finally got on the plane. Then they wouldn't let it take off. They announced that Brian Epstein and our road manager Mal Evans would have to get off the plane.

"We sat there for what seemed like eternity. Finally they got back and they let the plane go. But they took all the money we earned at the concerts from us."

|

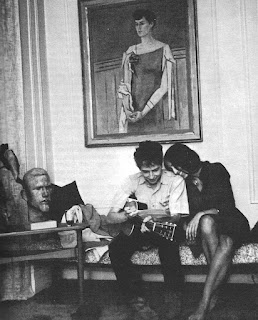

| George and sitar master Ravi Shankar |

On their return from Manila, The Beatles made their first brief visit to India, where George pursued his interest in the sitar, first used on Rubber Soul's Norwegian Wood. This resulted in the Indian raga-influenced track 'Love You To'.

It is the wide variety of styles and the sheer quality of the songs that is so remarkable about Revolver. Even Yellow Submarine was "perfectly in tune with Ringo's persona," said Clarke. "It's simplicity was engaging, rather than dumb."

Yellow Submarine certainly captured the imagination of a younger audience. I started junior school in the Autumn of 1966 and one of my abiding memories is sitting next to the window in my classroom and hearing a young pre-schooler in his back garden singing "We all live in a Yellow Submarine" over and over again.

|

| The American version was significantly shorter |

Yellow Submarine aside, there was a maturity about the songwriting and the subject matter. The extra time in the studio allowed the band to work on arrangements and to get the bass and drums sounding more solid. Most importantly, it gave them the freedom to experiment, which culminated in the album's final statement, Tomorrow Never Knows.

|

| Ringo created an iconic drum track |

There is all manner of sound effects, sped up and run backwards - primitive stuff by today's standards, but an act of true artistic creation in the context of the very basic analogue recording techniques they had at their disposal.

The willingness to not only try new ideas, but work out a way of getting the required sounds, is credited to Geoff Emerick, then just 20 years old and newly installed as The Beatles engineer, working under producer George Martin's direction.

According to Mark Lewinsohn's book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, "Geoff walked in green, but because he knew no rules, tried different techniques. The chemistry of George Martin and Geoff was perfect. With another producer and engineer, things would have turned out quite differently."

The Beatles all had their own home tape machines and Emerick recalled that Paul in particular would come into studio 3 at Abbey Road with little reels of tape saying 'listen to this'.

"We did a live mix of all the loops," remembered George Martin. "All over the studios we had people spooling them onto machines with pencils, while Geoff did the balancing. There were many other hands controlling the panning".

This was a performance in itself. "I laid all the loops onto the multi-track recorder and played the faders like a modern-day synthesiser," said Emerick.

The solution to John's request to sound like the Dalai Lama on top of a mountain was to feed his vocal through a Leslie speaker. "It meant breaking into the circuitry," said Emerick. "I remember the surprise on our faces when the voice came out of the speaker. After that, they wanted everything shoved through the Leslie!"

Sometime in the 1980s, this hierarchy changed and Revolver eclipsed Sgt. Pepper, to judge from lists compiled of the greatest all-time records.

In 1985, hipsters had hijacked the NME listings, placing John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band album at number 9, two places above Revolver. (Yeah, right. I mean, come on). And Sgt. Pepper? Nowhere to be seen in the '85 top 100.

But by 1993, a degree of sanity had been restored

to the NME writers' list, with Revolver up to Number 2 behind Pet

Sounds. Sgt. Pepper was back in at 33.

However, this new mature and experimental sound was something many Beatles fans found less appealing. This was a long way from "She Loves You, yeah yeah yeah!" though it would be a few more months before their loyalty was severely tested.

The following year, during the making of Sgt. Pepper, a Life Magazine profile noted that the group "are stepping far

ahead of their audience," but the possibility of losing support "does

not bother them in the least."

Elsewhere on this blog:

LIFE magazine reports on 'The New Far-out Beatles', 1967

Sgt. Pepper Is The Beatles - Who Knew?

At Home With the Lennons, 1967

A Night With John Lennon - The Fab Faux at Radio City Music Hall